Newspapers - 1940s - Evacuees Page 2

Don't Forget Your Gas Mask...

By PAM HOBBS

UPDATED: 20:00, 11 July 2009

In June 1940, when Britain was under imminent threat of German invasion, ten-year-old Pam Hobbs and her sister Iris were evacuated from the Essex coast to Derbyshire – along with 20,000 other children – with just two days’ warning. Here, she recalls the kindness and hardship she encountered during her two years away from home

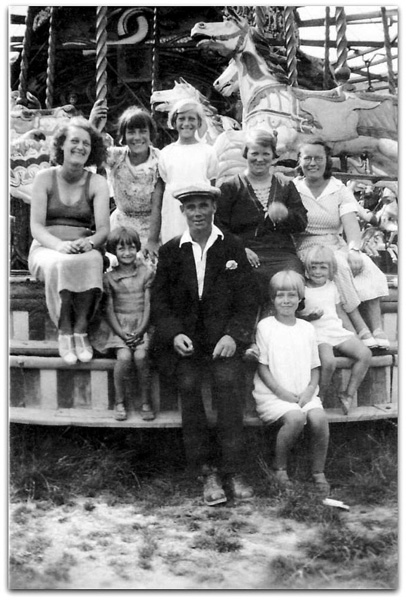

From left: Pam Hobbs, her sister Iris and a friend at Kirk Langley

We were instructed to assemble at school wearing name tags and carrying gas masks and a small case apiece containing a change of clothes. Few families on our council estate in Leigh-on-Sea owned suitcases, so most had brown paper carrier bags or pillowcases.

My 11-year-old sister Iris and I had burlap sacks, which my father had been using for sandbags to reinforce buildings along the seafront. Buses shuttled us between our school and the nearest major railway station, where we boarded trains headed north. Then, from various stops in Derbyshire, coaches took us in small groups to outlying communities.

A DERBYSHIRE DAIRY TALE

In the one-room village school in Charbury, around 15 of us lined up for prospective foster parents to pick us over, much as they would select fruit at the market. Pretty little girls and strong boys were the first to be chosen. Iris and I were neither.

At the best of times we looked pleasant and healthy, but not what you might call desirable. I was becoming hopeful of being sent back home when Joe and Cissy Simpson came in.

‘Eh, lass,’ Cissy said to me. ‘Will ye like to come home wi’ us?’

‘My dad says we have to stick together,’ said Iris

somewhat ungraciously.

‘Well, then, I’ll take the two of yer,’ Cissy said.

'It was some comfort to find my sister in bed beside me that first morning, but everything else seemed wrong'

It was some comfort to find Iris in bed beside me the next morning, but everything else seemed wrong. Barnyard smells outside the window, crowing cocks, mooing cows so close they appeared to be right in our room. Downstairs, Cissy was lifting small loaves from the hearth, her face wreathed in perspiration.

‘There ye are,’ she beamed. ‘I was just coming for you.’

I blurted out that I needed a lav.

‘Off ye run then. Everything ye needs is down there.’

The little lavatory shed was at the end of the long garden, but was spotlessly clean, with an enamel jug of water beside the wooden seat. Not sure whether this was to wash in or to flush, I left it for Iris to decide.

Aunty Ciss, as she told us to call her, explained that Uncle Joe worked in the nearby colliery. At the end of the day, she said, he would come home as black as the coal he dug, and she would fill a tin bath with hot water for him beside the fire. We thought he seemed far worse off than our dad, who at least had a proper bathroom.

With the summer holidays approaching, we had no formal schooling at first. Instead our chores included running errands to the vicar and to a neighbouring farm. My favourite place was the farm, where I would take a metal billycan every day

for our milk. I’d lie on the grass listening to the buzz of small creatures I knew so little about. I marvelled at the primroses and violets growing wild. I learned how to milk a cow and knew the wonder of lifting eggs from beneath the soft warm bodies of hens.

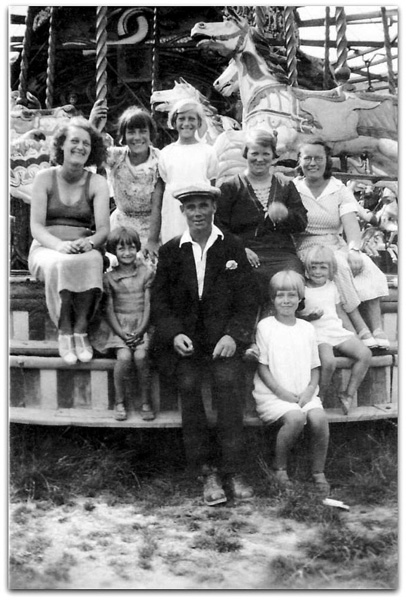

The Hobbs sisters (clockwise from left) Rose, Kath, Violet, Edie, Pam, Connie and Iris

with their parents in Southend-on-Sea in the 1930s

At the junior school across the road, when our education resumed in September, I was fortunate in that its only teacher,

Mr Farrow, liked me. Perhaps, in a class where most pupils were destined to work in the colliery or become farmhands,

it was my keenness to learn that caught his attention.

For whatever reason, he began tutoring me for a scholarship exam to Westcliff High School for Girls – my local Essex high school – which I took in a nearby town the following spring.

Sundays were the one time when I really wanted to be at home in Leigh-on-Sea with my six older sisters, in the happy confusion of our crowded front room, with dinner sizzling in the oven, and Dad almost, but not quite, winning the football pools. Sundays were no fun at all in Charbury, which was a very religious household: we wore our best clothes and weren’t allowed to play or read our comics.

'Sundays were the one time when I really wanted to be home in Leigh-on-Sea, in the happy confusion of our crowded front room'

Christmas was equally cheerless. No crackers to be pulled, no paper hats, no cheap decorations from Petticoat Lane. When Uncle Joe gave us a wonderful sledge – fire-engine red with a hooter he had scrounged from heaven knows where – a scowling Cissy stepped in to say that church was in 15 minutes and he could take ‘that thing’ outside until tomorrow.

Most of the time, though, Cissy seemed to enjoy having two ready-made daughters. (She told us the day after we arrived that, having never been blessed with children of their own, she and Joe had thanked God on their knees for sending us to them.) Our lack of interest in religion aside, we caused her little angst. For my part, I loved nothing more than to curl up and read books borrowed from Mr Farrow’s house, or to write lengthy letters home.

Stories of the Blitz filtered through to us in letters back, but none of the details were given to us. And it was scandal, not bombs, that forced us from our homes again that summer. When a naval officer from a local family molested one of the evacuees, and she reported it, hostility was directed at all the evacuees for the shame it was felt they had brought on the village. The authorities decided we should be relocated.

TRADING UP IN KIRK LANGLEY

Once again we found ourselves sitting in a school hall. Most of the good billets had been taken a year ago: now villagers had been asked to open their doors, and hearts, a little wider. Suddenly a short, round man burst through the door in baggy old tweed trousers and muddy brown boots…

‘Car’s this way, young ladies.’

‘Crikey, he’s got a motor,’ said Iris, grinning from ear to ear.

‘My wife Min will be really pleased to see I’ve brought two instead of one,’ Mr Dean (‘Call me Uncle Fred’) assured us, stopping in front of an ivy-covered house. We walked into a room where a table was set with plates of iced cakes and tall frosted glasses of lemonade.

Vera, the housekeeper, led us upstairs to two bedrooms: we could have one each or share and keep the other to play in. We decided to share. The sense that our lives had taken us into a fairy-tale world continued when Fred took us on a tour of the orchard, the duck pond and chicken coops. So much space!

Aunty Min (left); Iris and Pam in the garden at Leigh-on-Sea in 1945

Fred and Min Dean had longed for children of their own, and despite her crippling arthritis, they filled their lives with love and laughter. They encouraged us to invite other evacuees to join us in our play room, where we’d practise dance steps to the wireless, and, most Saturdays, the Deans had their own friends and relatives drop by. Vera would spread the worn oak dining table with plates of cold pork and ham, buttery new potatoes and bowls of fresh salad from the garden. And I had never seen so many fruit pies, custard tarts and sponge cakes.

I no longer hovered at the end of the drive waiting for the postman. The truth was, I read Mum’s news with a twinge of guilt. Here we were with all this food, while she went on about an extra piece of cod slipped to her from under the counter. A part of me didn’t want to be back at Kent Street sharing the shortages and bombs.

Then, towards the end of our happy, carefree summer, the postman brought me a congratulatory card from my family. I had passed the scholarship for Westcliff High School, which was now evacuated to Chapel-in-le-Frith, near Buxton.

I was distraught. How could everyone expect me to leave my sister – and the Deans, who loved me as their own? Uncle Fred made frantic phone calls, trying to get me into a Derby high school instead. But the scholarship was for Westcliff. I had to report to Chapel within two weeks or forfeit the place.

HIGH SCHOOL AND LOWS

It seems inconceivable today that an 11-year-old would be put on a train and told to disembark at a town she knew only from its name on a postcard. I adjusted my hat and was putting the postcard in my blazer pocket when I heard a voice booming down the platform: ‘Are you Pamela Hobbs?’

‘Yes, miss.’

‘Well, old thing, we do not wear our hats like that.’ In one swift movement the stocky figure straightened my offending panama. ‘And I am not “miss”. I am Miss White.’

Outside the station in Chapel-in-le-Frith was a pony and trap, in which we arrived at the impressive stone house where first-years stayed until billets could be found for them. I had no wish to leave: I loved the boarding-school atmosphere, having other girls to join for homework sessions and space of my own when I wanted it. Finally, though, a billet was found for me in a local home with another pupil called Monica Granger.

We were initially lodged with a young couple and their two-year-old child in a tiny terraced house. It suited us fine, until Monica’s mother arrived and declared herself unhappy about the cramped sleeping arrangements, which involved Monica using the couple’s bed while the husband was working night shifts at the local Ferodo factory. (Monica wasn’t a scholarship girl like me: back home in Essex, Daddy paid a handsome fee to send her to Westcliff.)

Pam's parents pose at the front gate in Essex

Now regarded as trouble-makers, we were moved on yet again, and ended up in a house on the dreariest of council estates. The eight months or so spent in the Barker home are the worst I can remember in my life. The unheated, stone-floored scullery became our home.

After school we did our homework at its scrubbed table by the light of one dim yellow bulb. At the onset of cold weather Mum sent money to Mrs Barker for a tin of ointment for my chilblains. She denied receiving it. After one bad bout of tonsillitis I began receiving ten-shilling notes in my letters from home. Mrs Barker insisted on keeping the money safe – so safe that I never saw it again.

By January my toes were a mass of chilblains that kept me awake most nights and, by spring, I had become very thin. I was now perpetually hungry. Mrs Barker kept our ration books in her battered handbag and the scullery larder was locked with a padlock.

'I was perpetually hungry. Our landlady kept our ration books in her handbag and the scullery larder was padlocked'

The shortage of food in our foster home was made more tolerable by snacks donated inadvertently by teachers (we volunteered to wash up the staff-room lunch, which provided us with discarded apple cores, pickles and bread crusts) and the occasional sweets sent by our mothers. But these rarely reached us.

Parcels that arrived while we were at school were always opened and left on the scullery table. New vests, socks and gloves went untouched, but more often than not the sweets were gone. When challenged, Mrs Barker would blithely tell us we couldn’t trust the postmen these days.

Towards the end of our stay, I asked Mrs Barker why she had volunteered to have us. ‘It was you or two Irish workmen,’ she told me, ‘and I made the wrong choice.’ For the first time in my life I knew what it was like to be unwanted. HOME AGAIN

By June 1942 Hitler was on the run. The threat of invasion had passed, and the entire school was returning to Westcliff that summer. Iris, now 14, had already gone home to our parents and got herself a job at Woolworths.

For me it would mean the beginning of a new era. Evacuation had been a great leveller. In Chapel we were all in it together: sharing, joking, grumbling, looking after ourselves and each other. Now most of my peers were returning to spacious homes, while I would go back to a crowded council house. For some, the war would continue to reduce the gulf between the classes, but for me it was about to be widened.

It was two years since I had left home as a nervous child hanging on to Iris. Now the Chalkwell station platform was choked with mothers craning to catch sight of returning daughters in a sea of girls all dressed alike.

When Dad finally arrived, it was on his bicycle, pulling a wooden box on two large pram wheels. Not wanting Mum and me to struggle with luggage on a crowded bus, he had made the carrier specially, and the journey home again would take him at least an hour. To my discredit all I could think was, ‘Thank God most of the parents and teachers have already left the station.’

For months I had dreamt of being home with my family in a noisy kitchen and cosy front room, but our little house seemed cheerless now. Nothing was the same. Not my family, not the daily routine – and definitely not me.

POSTSCRIPT

Pam Hobbs was still at Westcliff High School when the war ended in 1945. She emigrated to Canada in 1950. She is married with three daughters, and works as a journalist. Iris got married in Essex in 1952, and Fred and Min Dean came to the wedding.

|

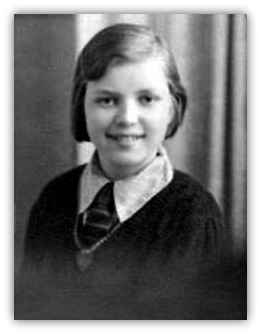

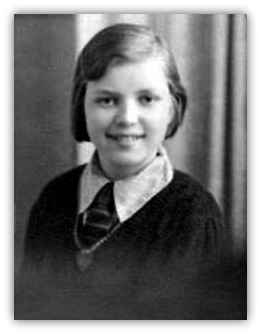

Pam as a schoolgirl |

This is an edited extract from Don't Forget to Write by Pam Hobbs ISBN 9780091932503

|